also time is something which is part of Creation but it seems assumed that the time of Earth and Heaven are the same

the major secular discussion is Heidigger History of Concept of TIme

Time

| Time |

|---|

|

| Current time (update) |

| 17:18, 28 December 2017 (UTC) |

| Classical mechanics |

|---|

Time is the indefinite continued progress of existence and events that occur in apparently irreversible succession from the past through the present to the future.[1][2][3] Time is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequence events, to compare the duration of events or the intervals between them, and to quantify rates of change of quantities in material reality or in the conscious experience.[4][5][6][7] Time is often referred to as a fourth dimension, along with three spatial dimensions.[8]

Time has long been an important subject of study in religion, philosophy, and science, but defining it in a manner applicable to all fields without circularityhas consistently eluded scholars.[2][6][7][9][10][11] Nevertheless, diverse fields such as business, industry, sports, the sciences, and the performing arts all incorporate some notion of time into their respective measuring systems.[12][13][14]

Two contrasting viewpoints on time divide prominent philosophers. One view is that time is part of the fundamental structure of the universe—a dimensionindependent of events, in which events occur in sequence. Isaac Newtonsubscribed to this realist view, and hence it is sometimes referred to as Newtonian time.[15][16] The opposing view is that time does not refer to any kind of "container" that events and objects "move through", nor to any entity that "flows", but that it is instead part of a fundamental intellectual structure (together with space and number) within which humans sequence and compare events. This second view, in the tradition of Gottfried Leibniz[17] and Immanuel Kant,[18][19] holds that time is neither an event nor a thing, and thus is not itself measurable nor can it be travelled.

Immanuel Kant, Critique of Pure Reason (1781), trans. Vasilis Politis (London: Dent., 1991), p.54.

Linear and cyclical time

Ancient cultures such as Incan, Mayan, Hopi, and other Native American Tribes - plus the Babylonians, Ancient Greeks, Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and others - have a concept of a wheel of time: they regard time as cyclical and quantic,[clarification needed] consisting of repeating ages that happen to every being of the Universe between birth and extinction.[citation needed]

In general, the Islamic and Judeo-Christian world-view regards time as linear[51] and directional,[52]beginning with the act of creation by God. The traditional Christian view sees time ending, teleologically,[53] with the eschatological end of the present order of things, the "end time".

In the Old Testament book Ecclesiastes, traditionally ascribed to Solomon (970–928 BC), time (as the Hebrew word עידן, זמן `iddan(age, as in "Ice age") zĕman(time) is often translated) was traditionally regarded[by whom?] as a medium for the passage of predestined events.[citation needed](Another word, زمان" זמן" zamān, meant time fit for an event, and is used as the modern Arabic, Persian, and Hebrew equivalent to the English word "time".)

Time in Greek mythology

The Greek language denotes two distinct principles, Chronos and Kairos. The former refers to numeric, or chronological, time. The latter, literally "the right or opportune moment", relates specifically to metaphysical or Divine time. In theology, Kairos is qualitative, as opposed to quantitative.[citation needed]

In Greek mythology, Chronos (Ancient Greek: Χρόνος) is identified as the Personification of Time. His name in Greek means "time" and is alternatively spelled Chronus (Latin spelling) or Khronos. Chronos is usually portrayed as an old, wise man with a long, gray beard, such as "Father Time". Some English words whose etymological root is khronos/chronos include chronology, chronometer, chronic, anachronism, synchronise, and chronicle.

Time in Kabbalah

According to Kabbalists, "time" is a paradox[54] and an illusion.[55] Both the future and the past are recognised to be combined and simultaneously present.

Philosophy

Two distinct viewpoints on time divide many prominent philosophers. One view is that time is part of the fundamental structure of the universe, a dimension in which events occur in sequence. Sir Isaac Newton subscribed to this realist view, and hence it is sometimes referred to as Newtonian time.[16] An opposing view is that time does not refer to any kind of actually existing dimension that events and objects "move through", nor to any entity that "flows", but that it is instead an intellectual concept (together with space and number) that enables humans to sequence and compare events.[56] This second view, in the tradition of Gottfried Leibniz[17] and Immanuel Kant,[18][19] holds that space and time "do not exist in and of themselves, but ... are the product of the way we represent things", because we can know objects only as they appear to us.

Furthermore, it may be that there is a subjective component to time, but whether or not time itself is "felt", as a sensation, or is a judgment, is a matter of debate.[2][6][7][57][58]

The Vedas, the earliest texts on Indian philosophy and Hindu philosophy dating back to the late 2nd millennium BC, describe ancient Hindu cosmology, in which the universe goes through repeated cycles of creation, destruction and rebirth, with each cycle lasting 4,320 million years.[59] Ancient Greek philosophers, including Parmenides and Heraclitus, wrote essays on the nature of time.[60] Plato, in the Timaeus, identified time with the period of motion of the heavenly bodies. Aristotle, in Book IV of his Physica defined time as 'number of movement in respect of the before and after'.[61]

In Book 11 of his Confessions, St. Augustine of Hippo ruminates on the nature of time, asking, "What then is time? If no one asks me, I know: if I wish to explain it to one that asketh, I know not." He begins to define time by what it is not rather than what it is,[62] an approach similar to that taken in other negative definitions. However, Augustine ends up calling time a "distention" of the mind (Confessions 11.26) by which we simultaneously grasp the past in memory, the present by attention, and the future by expectation.

In contrast to ancient Greek philosophers who believed that the universe had an infinite past with no beginning, medieval philosophers and theologians developed the concept of the universe having a finite past with a beginning. This view is shared by Abrahamic faiths as they believe time started by creation, therefore the only thing being infinite is God and everything else, including time, is finite.

Isaac Newton believed in absolute space and absolute time; Leibniz believed that time and space are relational.[63] The differences between Leibniz's and Newton's interpretations came to a head in the famous Leibniz–Clarke correspondence.

Time is not an empirical concept. For neither co-existence nor succession would be perceived by us, if the representation of time did not exist as a foundation a priori. Without this presupposition we could not represent to ourselves that things exist together at one and the same time, or at different times, that is, contemporaneously, or in succession.

“

”

Immanuel Kant, in the Critique of Pure Reason, described time as an a priori intuition that allows us (together with the other a priori intuition, space) to comprehend sense experience.[64] With Kant, neither space nor time are conceived as substances, but rather both are elements of a systematic mental framework that necessarily structures the experiences of any rational agent, or observing subject. Kant thought of time as a fundamental part of an abstract conceptual framework, together with space and number, within which we sequence events, quantify their duration, and compare the motions of objects. In this view, time does not refer to any kind of entity that "flows," that objects "move through," or that is a "container" for events. Spatial measurements are used to quantify the extent of and distances between objects, and temporal measurements are used to quantify the durations of and between events. Time was designated by Kant as the purest possible schema of a pure concept or category.

Henri Bergson believed that time was neither a real homogeneous medium nor a mental construct, but possesses what he referred to as Duration. Duration, in Bergson's view, was creativity and memory as an essential component of reality.[65]

According to Martin Heidegger we do not exist inside time, we are time. Hence, the relationship to the past is a present awareness of having been, which allows the past to exist in the present. The relationship to the future is the state of anticipating a potential possibility, task, or engagement. It is related to the human propensity for caring and being concerned, which causes "being ahead of oneself" when thinking of a pending occurrence. Therefore, this concern for a potential occurrence also allows the future to exist in the present. The present becomes an experience, which is qualitative instead of quantitative. Heidegger seems to think this is the way that a linear relationship with time, or temporal existence, is broken or transcended.[66] We are not stuck in sequential time. We are able to remember the past and project into the future—we have a kind of random access to our representation of temporal existence; we can, in our thoughts, step out of (ecstasis) sequential time.[67]

Time as "unreal"

In 5th century BC Greece, Antiphon the Sophist, in a fragment preserved from his chief work On Truth, held that: "Time is not a reality (hypostasis), but a concept (noêma) or a measure (metron)." Parmenides went further, maintaining that time, motion, and change were illusions, leading to the paradoxes of his follower Zeno.[68] Time as an illusion is also a common theme in Buddhist thought.[69][70]

J. M. E. McTaggart's 1908 The Unreality of Time argues that, since every event has the characteristic of being both present and not present (i.e., future or past), that time is a self-contradictory idea (see also The flow of time).

These arguments often center on what it means for something to be unreal. Modern physicists generally believe that time is as real as space—though others, such as Julian Barbour in his book The End of Time, argue that quantum equations of the universe take their true form when expressed in the timeless realm containing every possible now or momentary configuration of the universe, called 'platonia' by Barbour.[71]

A modern philosophical theory called presentism views the past and the future as human-mind interpretations of movement instead of real parts of time (or "dimensions") which coexist with the present. This theory rejects the existence of all direct interaction with the past or the future, holding only the present as tangible. This is one of the philosophical arguments against time travel. This contrasts with eternalism (all time: present, past and future, is real) and the growing block theory(the present and the past are real, but the future is not).

Physical definition

| Classical mechanics |

|---|

Until Einstein's reinterpretation of the physical concepts associated with time and space, time was considered to be the same everywhere in the universe, with all observers measuring the same time interval for any event.[72] Non-relativistic classical mechanics is based on this Newtonian idea of time.

Einstein, in his special theory of relativity,[73] postulated the constancy and finiteness of the speed of light for all observers. He showed that this postulate, together with a reasonable definition for what it means for two events to be simultaneous, requires that distances appear compressed and time intervals appear lengthened for events associated with objects in motion relative to an inertial observer.

The theory of special relativity finds a convenient formulation in Minkowski spacetime, a mathematical structure that combines three dimensions of space with a single dimension of time. In this formalism, distances in space can be measured by how long light takes to travel that distance, e.g., a light-year is a measure of distance, and a meter is now defined in terms of how far light travels in a certain amount of time. Two events in Minkowski spacetime are separated by an invariant interval, which can be either space-like, light-like, or time-like. Events that have a time-like separation cannot be simultaneous in any frame of reference, there must be a temporal component (and possibly a spatial one) to their separation. Events that have a space-like separation will be simultaneous in some frame of reference, and there is no frame of reference in which they do not have a spatial separation. Different observers may calculate different distances and different time intervals between two events, but the invariant interval between the events is independent of the observer (and his or her velocity).

Classical mechanics

In non-relativistic classical mechanics, Newton's concept of "relative, apparent, and common time" can be used in the formulation of a prescription for the synchronization of clocks. Events seen by two different observers in motion relative to each other produce a mathematical concept of time that works sufficiently well for describing the everyday phenomena of most people's experience. In the late nineteenth century, physicists encountered problems with the classical understanding of time, in connection with the behavior of electricity and magnetism. Einstein resolved these problems by invoking a method of synchronizing clocks using the constant, finite speed of light as the maximum signal velocity. This led directly to the result that observers in motion relative to one another measure different elapsed times for the same event.

Spacetime

Time has historically been closely related with space, the two together merging into spacetime in Einstein's special relativity and general relativity. According to these theories, the concept of time depends on the spatial reference frame of the observer, and the human perception as well as the measurement by instruments such as clocks are different for observers in relative motion. For example, if a spaceship carrying a clock flies through space at (very nearly) the speed of light, its crew does not notice a change in the speed of time on board their vessel because everything traveling at the same speed slows down at the same rate (including the clock, the crew's thought processes, and the functions of their bodies). However, to a stationary observer watching the spaceship fly by, the spaceship appears flattened in the direction it is traveling and the clock on board the spaceship appears to move very slowly.

On the other hand, the crew on board the spaceship also perceives the observer as slowed down and flattened along the spaceship's direction of travel, because both are moving at very nearly the speed of light relative to each other. Because the outside universe appears flattened to the spaceship, the crew perceives themselves as quickly traveling between regions of space that (to the stationary observer) are many light years apart. This is reconciled by the fact that the crew's perception of time is different from the stationary observer's; what seems like seconds to the crew might be hundreds of years to the stationary observer. In either case, however, causality remains unchanged: the past is the set of events that can send light signals to an entity and the future is the set of events to which an entity can send light signals.[74][75][76]

Time dilation

Einstein showed in his thought experiments that people travelling at different speeds, while agreeing on cause and effect, measure different time separations between events, and can even observe different chronological orderings between non-causally related events. Though these effects are typically minute in the human experience, the effect becomes much more pronounced for objects moving at speeds approaching the speed of light. Subatomic particles exist for a well known average fraction of a second in a lab relatively at rest, but when travelling close to the speed of light they are measured to travel farther and exist for much longer than when at rest. According to the special theory of relativity, in the high-speed particle's frame of reference, it exists, on the average, for a standard amount of time known as its mean lifetime, and the distance it travels in that time is zero, because its velocity is zero. Relative to a frame of reference at rest, time seems to "slow down" for the particle. Relative to the high-speed particle, distances seem to shorten. Einstein showed how both temporal and spatial dimensions can be altered (or "warped") by high-speed motion.

Einstein (The Meaning of Relativity): "Two events taking place at the points A and B of a system K are simultaneous if they appear at the same instant when observed from the middle point, M, of the interval AB. Time is then defined as the ensemble of the indications of similar clocks, at rest relative to K, which register the same simultaneously."

Einstein wrote in his book, Relativity, that simultaneity is also relative, i.e., two events that appear simultaneous to an observer in a particular inertial reference frame need not be judged as simultaneous by a second observer in a different inertial frame of reference.

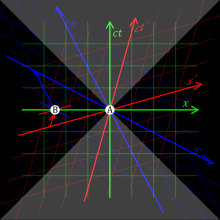

Relativistic time versus Newtonian time

The animations visualise the different treatments of time in the Newtonian and the relativistic descriptions. At the heart of these differences are the Galilean and Lorentz transformations applicable in the Newtonian and relativistic theories, respectively.

In the figures, the vertical direction indicates time. The horizontal direction indicates distance (only one spatial dimension is taken into account), and the thick dashed curve is the spacetime trajectory ("world line") of the observer. The small dots indicate specific (past and future) events in spacetime.

The slope of the world line (deviation from being vertical) gives the relative velocity to the observer. Note how in both pictures the view of spacetime changes when the observer accelerates.

In the Newtonian description these changes are such that time is absolute:[77] the movements of the observer do not influence whether an event occurs in the 'now' (i.e., whether an event passes the horizontal line through the observer).

However, in the relativistic description the observability of events is absolute: the movements of the observer do not influence whether an event passes the "light cone" of the observer. Notice that with the change from a Newtonian to a relativistic description, the concept of absolute time is no longer applicable: events move up-and-down in the figure depending on the acceleration of the observer.

Arrow of time

Time appears to have a direction—the past lies behind, fixed and immutable, while the future lies ahead and is not necessarily fixed. Yet for the most part the laws of physics do not specify an arrow of time, and allow any process to proceed both forward and in reverse. This is generally a consequence of time being modelled by a parameter in the system being analysed, where there is no "proper time": the direction of the arrow of time is sometimes arbitrary. Examples of this include the cosmological arrow of time, which points away from the Big Bang, CPT symmetry, and the radiative arrow of time, caused by light only travelling forwards in time (see light cone). In particle physics, the violation of CP symmetryimplies that there should be a small counterbalancing time asymmetry to preserve CPT symmetry as stated above. The standard description of measurement in quantum mechanics is also time asymmetric (see Measurement in quantum mechanics). The second law of thermodynamics states that entropy must increase over time (see Entropy). This can be in either direction - Brian Greene theorizes that, according to the equations, the change in entropy occurs symmetrically whether going forward or backward in time. So entropy tends to increase in either direction, and our current low-entropy universe is a statistical aberration, in the similar manner as tossing a coin often enough that eventually heads will result ten times in a row. However, this theory is not supported empirically in local experiment.[78]

Quantized time

Time quantization is a hypothetical concept. In the modern established physical theories (the Standard Model of Particles and Interactions and General Relativity) time is not quantized.

Planck time (~ 5.4 × 10−44 seconds) is the unit of time in the system of natural units known as Planck units. Current established physical theories are believed to fail at this time scale, and many physicists expect that the Planck time might be the smallest unit of time that could ever be measured, even in principle. Tentative physical theories that describe this time scale exist; see for instance loop quantum gravity.

Time travel

Time travel is the concept of moving backwards or forwards to different points in time, in a manner analogous to moving through space, and different from the normal "flow" of time to an earthbound observer. In this view, all points in time (including future times) "persist" in some way. Time travel has been a plot device in fiction since the 19th century. Travelling backwards in time has never been verified, presents many theoretical problems, and may be an impossibility.[79] Any technological device, whether fictional or hypothetical, that is used to achieve time travel is known as a time machine.

A central problem with time travel to the past is the violation of causality; should an effect precede its cause, it would give rise to the possibility of a temporal paradox. Some interpretations of time travel resolve this by accepting the possibility of travel between branch points, parallel realities, or universes.

Another solution to the problem of causality-based temporal paradoxes is that such paradoxes cannot arise simply because they have not arisen. As illustrated in numerous works of fiction, free will either ceases to exist in the past or the outcomes of such decisions are predetermined. As such, it would not be possible to enact the grandfather paradoxbecause it is a historical fact that your grandfather was not killed before his child (your parent) was conceived. This view doesn't simply hold that history is an unchangeable constant, but that any change made by a hypothetical future time traveller would already have happened in his or her past, resulting in the reality that the traveller moves from. More elaboration on this view can be found in the Novikov self-consistency principle.

Time perception

The specious present refers to the time duration wherein one's perceptions are considered to be in the present. The experienced present is said to be ‘specious’ in that, unlike the objective present, it is an interval and not a durationless instant. The term specious present was first introduced by the psychologist E.R. Clay, and later developed by William James.[80]

berah